How do we choose representatives?

Australia’s Electoral System

The Australian electoral system, overseen by the independent Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), is among the most innovative in the world.

Australia pioneered the secret ballot in 1856 through colonial elections in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania; compulsory voting for all adult citizens was introduced in 1918.

The AEC ensures access to the polls is no barrier to voting by operating expansive early voting, providing postal ballots, and offering accessibility options for people living with disability and mobility issues.

The AEC also evaluates the performance of the electoral system and suggests and implements improvements. Most recently this included 2016 changes to the structure of voting in the Senate that aimed to increase the congruency between voters’ preferences and the result after redistribution.

In 1902 Australia became the first country to grant universal suffrage to all women citizens: the right to vote and to nominate as a candidate for parliament. However, Australia retains the unfortunate moniker of the longest period between granting universal suffrage and electing a woman member to its federal parliament. Dame Enid Lyons (House of Representatives, member for what is now Braddon) and Dame Dorothy Tangney (Senate, Western Australia) were elected in 1943.

Additionally, it would be misleading to present these achievements as facts without also noting that First Nations men and women were federally excluded from universal suffrage until 1962.

The current electoral system does not include any constitutional or legislative special measures guaranteeing representation of non-traditional political actors.

| Variable | House of Representatives | Senate |

|---|---|---|

| District Magnitude | Single Member Electorates | Multi-Member Electorates |

| Ballot structure | Exhaustive preferential | Optional preferential |

| Electoral formula | Absolute majority | Proportional plurality |

Political Parties as Gatekeepers

Australia’s liberal democratic electoral system relies on political parties to moderate the candidates that contest each election. Procedurally, such mediation requires evaluating the values, experience and ministerial potential of each candidate against each other in order to maintain philosophical consistency and party loyalty.

When traditional political actors were the only players in the political system, the moderating pre-selection process aimed to weed out those candidates the party decided were too philosophically radical, or too reactionary, for the electorate at large. This was possible due to a relative level of similarity in identity, experience, background and values. As more women and people of non-traditional political backgrounds and identities began to nominate for pre-selection, these calculations became more complicated: for example, how do you value the experience primary caregivers gain while they are out of the workforce?

Political parties have not adapted to this change, still relying on old metrics to evaluate candidate nominations. It would be easy to dismiss parties’ historic gatekeeper role as perpetuating inequalities in representation. The intuitive response is to move to a more primary based model in which power is distributed among more of the diverse, complex, electorate. Unfortunately, adjudicating candidates for representation will always involve a level of information asymmetry between high and low-information voters, a disparity that is exacerbated by the cognitive short-cuts we all use when making decisions faced with incomplete data.

Political parties will always have a gatekeeper role to play in order to ensure that the process is as fair and meritocratic as possible. In order to preserve any integrity in claiming unbiased pre-selections; however, parties must recognise the ways in which non-traditional political actors are structurally and culturally excluded from the political process and seek to remedy these barriers. They must become better at finding, training and evaluating candidates, at recognising philosophical blind-spots and challenges to diversity, and at creating transformative cultural change.

Barriers to entry

Non-traditional political actors face additional barriers to nomination and election to, and promotion within, parliament.

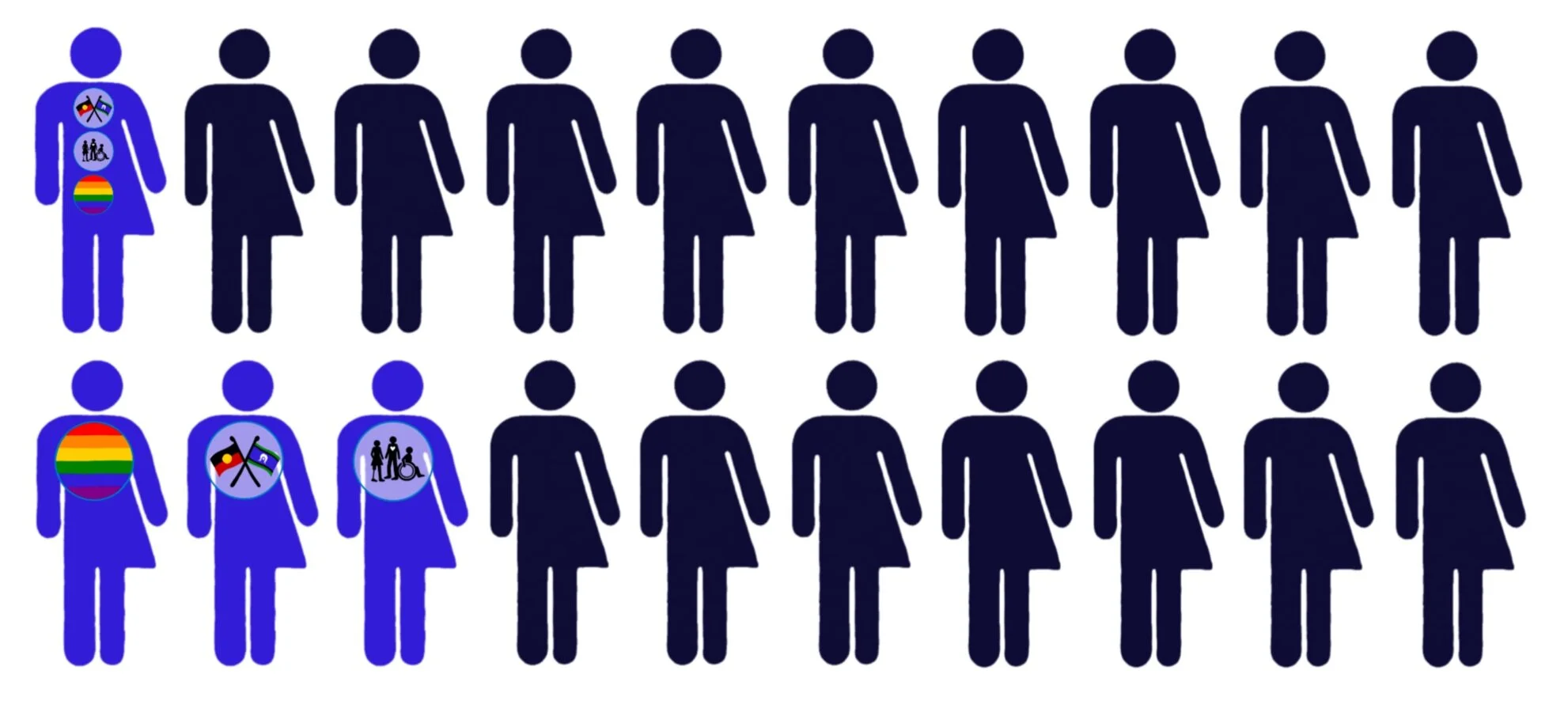

In Australia this group includes women, transgender and non-binary people; members of the LGBTQ+ community; First Nations Australians; culturally and linguistically diverse Australians including people identifying with a non-Christian faith; people living with a disability; younger Australians; people without a tertiary education; and people who were born into or live in relative socio-economic disadvantage.

Identity is complex and dynamic; the impacts of intersecting identities will vary according to individual and context. The barriers identified here are generalisable and will not apply to every individual running for parliament. Rather, they should be considered as potentialities without effective mitigation of which it will be impossible to achieve true equality of opportunity and meritocratic pre-selections.

Ideal candidate norms

Political parties are naturally risk-averse, often favouring electoral appeal over potential parliamentary skill when nominating candidates for election. This calculus leads to a preference for candidates that appear similar to those that have achieved electoral success historically. These practices and behaviours may be unconsciously reproduced through norms and conventions that go unchallenged within parties. Restricting metrics for candidate evaluation to those congruent with an ‘ideal-type’ may appear to be removing bias from the equation, but will necessarily favour those who were born with or have been able to develop similar identities and attributes to traditional political actors.

Non-traditional identities can be perceived to be a liability, with the potential for constituents to feel threatened by disruptions in the current distribution of power. Political parties may attempt to mitigate this disruption by nominating fewer candidates that belong to multiple identity groups rather than more candidates that only have a few non-traditional identity affiliations. This tokenistic practice is often performatively described as meritocratic but in reality obscures an ongoing concentration of power in the hands of the political elite.

Similarly, parties may be more likely to pre-select non-traditional candidates in marginal seats (‘marginal seat syndrome’). A member of parliament that holds a seat classified as marginal (>56%) focuses a greater portion of their resources on the retention of power than those assured incumbency through holding safe seats (60%+). MPs that do not face this additional burden are able to allocate those resources to building parliamentary networks and participating in parliamentary work: achieving the key objectives for parliamentary promotion much more quickly than their marginal seat colleagues.

Responsibility for the perpetuation of such practices does not lie solely with traditional political actors, but also with non-traditional political actors that have developed adaptive behaviours in order to succeed within an exclusionary environment. The calculus between challenging the status quo and losing the nomination, or adapting to the characteristics of those in power and winning nomination with a view to affecting culture at a parliamentary level, is complex and fraught with internal contradictions. It is impossible to say whether candidates will internalise adaptive behaviours such that they will be unable to make a cultural challenge in the future, but the intransigence of parliamentary culture suggests that this adaptive route has not been successful.

Pre-selection processes

The ‘secret garden’ of party pre-selection is largely informal and concealed from public scrutiny.

Pre-selection processes are set at the state level in each party and are generally not publicly available. Candidates are required to submit basic biographical details that are considered by panels drawn from the electorate branch they are seeking nomination for, but no standardised metric for evaluation is provided nor publicised.

Adjudicating candidate nominations in this way favours the ‘ideal-type’ candidate by relying on existing cognitive shortcuts. One of these pitfalls is the potential misrepresentation of confidence as competence: a gendered phenomenon that is exacerbated by the political environment.

Many nomination processes are predetermined by factional powerbrokers who inform the groups they control of the appropriate ballot preference order, even before the candidates have delivered speeches to the panel. This can limit the number of individuals candidates need to engage with to a handful of powerbrokers rather than potentially hundreds of panel members.

If non-traditional political actors are fortunate enough to have a champion in a position of power, or have managed to cultivate a strong network that influences or circumvents these powerbrokers, they can leverage this captive market to win nomination more easily. More likely; however, non-traditional political actors will not have had access to the resources needed to build these networks extensively and effectively.

Media

Non-traditional political actors are critiqued based on their diversion to the identity norm rather than the philosophical norm.

Women candidates and politicians face increased scrutiny over their parenting and appearance; ethnic, religious and cultural minorities are forced into being spokespeople for their communities; the ubiquitous ‘identity card’ is relied upon as a catch all dismissive remark to demands for equal treatment.

Party and parliamentary practices

Much like traditional actors have shaped the principled landscape of Australia’s political system, the practical aspects of our political institutions and processes have been gradually shaped by hegemonic forces.

Non-traditional political actors are more likely to face situations of precarity, for example:

Less disposable income, generational wealth and resources

Unstable housing conditions

Family instability

Educational difficulties, including insufficient resources

Disabilities and health problems, including substance abuse

Cultural clashes and difficulties

Religious discrimination

Discrimination against the LQBTQ+ community

Gendered violence, stereotyping and unconscious biases

Stereotype threat

Caring responsibilities

Each of these situations influences the opportunities available to the people affected by them. A single mother working three jobs to support her children will have fewer resources (time and finances) to expend on activities that may support her political ambitions: attending party meetings, fundraising events, campaigning activities.

This is compounded by the natural disadvantage non-traditional political actors face in network creation: informal networks that have political value under the current institutional arrangements are more prevalent and easily maintained among traditional political actors and those that can pass as TPAs.

Further, the flexibility that is required to ameliorate some of these disadvantages is rare in parliamentary politics. Family and caring responsibilities are given little consideration in planning events and sitting hours; cultural practices that deviate from the norm are rarely considered.

Platform priorities

The political game has been shaped by traditional actors. These actors have for centuries influenced the values that guide policy-making, the issues that are prioritised, and the ways decisions are communicated to the public.

Non-traditional political actors are therefore faced with a double bind: pitch their electoral appeal on a surrogate or issue based platform and risk being pigeonholed; or lean in to the adaptive behaviours that help them pass as non-threatening pseudo-traditional political actors. In either choice, NTPA contend with stereotyping and tokenism.

Political parties have in some ways reconciled themselves to the necessity for including identity-based claims in their election platform and have promoted these claims to varying degrees. However, these issues are rarely prioritised in platform construction as they, often unconsciously due to cognitive short-cuts, are perceived to be less electorally appealing than traditional campaign claims and methods.

Finance

Australian political parties and candidates are partially publicly funded by the AEC. This ensures that candidates who have access to private savings, loans or political party nominations are able to recoup a relative level of personal financial investment into their election campaigns. In 2011 private funding sources contributed around 80% of campaign and operating funds held by Australian political parties.

Non-traditional political actors are more likely to have limited access to, or lower levels of, these private sources of funding. In addition, private donors to political parties may pressure parties to nominate traditional political actors, or influence the allocation of resources within campaigns, by attaching informal conditions to financial contributions.

A large portion of election expenditure is obtained through fundraising. Effective fundraising requires initial investment into network and relationship building as well as the time and resources expended on actual fundraising events and practices. Non-traditional political actors with - for example - less stable incomes, caring responsibilities, smaller or less wealthy informal networks face additional barriers in accessing traditional fundraising models.