Identity in Representation

Identity is a function of existence: a complex, dynamic, subjective understanding of self shaped by our (internal) cognitive processes, emotional responses and (external) societal reactions to identity expression and performance. Identity markers are the characteristics that differentiate humans from each other; that inform our understanding of self and the way we organise into communities. It is not the characteristics themselves that are important but the ways in which we experience them: the nexus between identity markers as we prioritise, compromise and value them differently over time and in different spaces; and the networks that we create in doing so.

Measuring and evaluating identity markers provides a quantitative foundation from which to begin capturing the complexity of identity as a fluid, responsive, dynamic experience of self and community.

Identity in Society

It is impossible to develop an understanding of personal identity in a vacuum. Our identity formation is influenced by the reactions of others through material, social and emotional rewards or punishments allocated for conformity to normative behaviours.

We all, sometimes intentionally; sometimes unconsciously, perform our identities through the myriad decisions we make in a day. How we present ourselves to the world; how we engage with other individuals and groups; what we spend our time doing; how we allocate our financial resources: each decision sends a signal to others about what we value. The way these claims are responded to then influences the way we engage with the performance and audience into the future.

Identity Performances

Preferred name & pronouns

Mobility & accessibility aids

Clothing, hair & make-up

Speech patterns, vocabulary & accent

Expressions of faith & membership of religious communities

Education (formal and informal)

Occupation

Volunteering & charitable giving

Method of transport

Home type, location, art & furniture choice

Interests & hobbies

Participation in cultural groups & celebrations

Sporting team & player support preferences & participation

Pop culture and creative arts consumption (media and platform) & participation

Online presence

Social activity preferences

Restrictions to food and beverages

Every person will experience different social responses to their identity expression. These responses will change according to the audience, context, an individual’s stage of the lifecycle, and be influenced by broader social progress.

Social responses are additionally influenced by common narratives of identity: shared norms of engagement that provide the basis on which humans organise and relate to one another. Humans are by nature social beings, relying on communities for safety and security. Despite the pace at which we are able to complicate our environment our neural pathways and cognitive processes still largely reflect the tribal nature of early human society. As our environments become more complex through technological innovation and social progress these cognitive shortcuts assist us in prioritising attention towards the issues and resources that will bring the most benefit.

Cognitive shortcuts

Schemas and heuristics that organise and prioritise information to aid complex decision-making in situations of information asymmetry.

Representativeness heuristic : an individual is more likely to make a decision in favour of an option that closely resembles their own experience.

Homophily principle : individuals’ tendency to form communities with those similar to themselves.

Role congruity theory : individuals with perceived characteristics most closely aligned with social expectations of a position will be favoured in the election or appointment to the role.

Stereotype threat : individuals may unconsciously limit their potential in line with stereotypes about a group they belong to.

Trait inferences : an individual’s personality attributes are observed, categorised and used as a predictive heuristic for future behaviour.

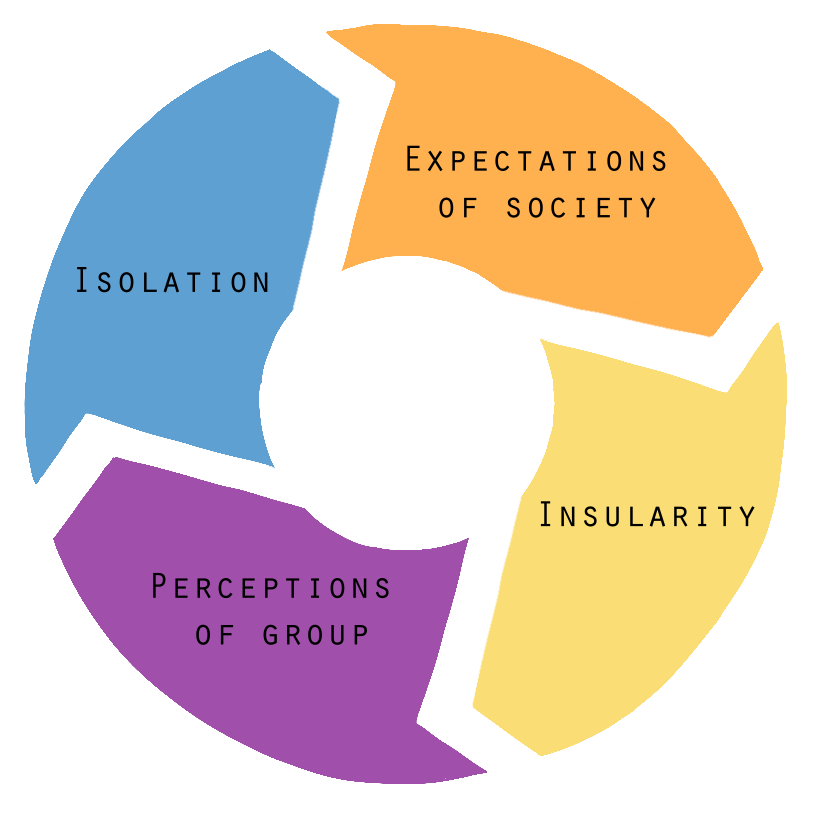

Seeking comfort through allegiances with those who share our characteristics, experiences and networks is not inherently dangerous: we seek these communities to limit the potential for cognitive dissonance between internal (personal) and external (societal) responses to our identity claims. However, the feedback loop between society and a group that feels isolated or ignored and consequently retreats further into itself, or a group that feels welcomed and opens itself to engagement with other groups, can perpetuate the exclusionary or inclusionary nature of these networks. This cycle manifests in three ways:

Network signals: discriminatory norms, heuristics and behaviours are activated by group membership.

Network information: individuals tend to develop more extreme views when exposed to groups that share premises and argument directionality.

Network logistics: Australians are becoming increasingly physically insular, influenced by declining leisure time and disposable income. This global trend has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Inclusionary networks

Exclusionary networks

Every individual is born into a set of relationships based on their identity characteristics. These relationships form the basis of our identity networks.

Identity Networks

The number, type and value of our identity networks changes over time as we move through the lifecycle. The direction and scope of our network development is defined by these cognitive shortcuts as well as the choices we make to accept or reject their influence.

These choices are constrained by the opportunities available to each individual by virtue of their existing social and financial capital: the more opportunities an individual has access to, the more diverse their networks will be; and personal, geographic and online limitations. Similarly, the more closely these identity networks conform to dominant societal norms the less conscious an individual will be of performing their identity correctly.

Identity politics is often dismissed as a victimisation strategy; a stylised marginality through which groups and individuals claim that they have been discriminated against on the basis of their identity. This argument falsely and disproportionately attributes identity politics to non-traditional political actors, both essentialising these actors by focusing on their identity claims and erasing the historic and contemporary identity claims made by traditional political actors. In reality, identity politics appear to be the domain of the marginalised because non-traditional political actors are more likely to be conscious of the way in which their identity operates within society.

Each of the networks we have access to comprises a different audience and requires behavioural adaptations to retain this access in accordance with network reactions. In reconciling these reactions we become more conscious of our identity: the more potentially aberrant a behaviour; the more contextually challenging a performance, the higher our identity consciousness will be. In contrast, individuals with identity markers that are largely consistent with dominant social norms may not experience the same level of awareness.

Identity congruity: the degree to which an individual’s identity is consistent with the dominant norms and behaviours of the networks and society to which they belong.

This is not only true of individuals but also of groups and systems. In representative terms, it is impossible to design an electoral system in which each representative is maximally diverse or identity conscious; however, it may be possible to design a system in which representative institutions are able to explicitly and normatively reflect the diversity of experiences and networks in the Australian population.

Identity in Politics

The effects of group behaviour are multiplied within the political system. Politicians rely on common narratives and cognitive shortcuts to frame their own political identities, campaigns and policies. This is exacerbated by parliamentarians’ existing network homogeneity. The hyper-partisan, high-stakes game of politics incentivises political actors to strengthen their internal communities, limiting representatives’ capacity to break the exclusionary cycles of network formation.

The 24-hour media cycle and proliferation of social media contributes to the fishbowl nature of contemporary politics. Incentivised by commercial interests to find and maintain drama in the political system, the media tends towards sensationalism and identity-based narratives. The same is true of political messaging that relies on common narratives to appeal to specific sections of the electorate: Menzies’ forgotten people, Howard’s battlers, Rudd’s working families, Tony’s tradies. Each of these slogans is designed to provoke an emotional response that activates these identities. The framing and distribution of such stories and messaging rely on viewers’ existing cognitive shortcuts and in turn perpetuate dominant norms and stereotypes.

In contrast, the symbolic power of the representation of non-traditional political actors lies in its capacity to provide new imagery for old narratives: to challenge the way cognitive shortcuts have embedded misrepresentations about their identity groups into our politics. Substantively, such representation should increase the diversity of perspectives in Parliament by decreasing the overlap of networks among parliamentarians and by increasing the pool of experiences from which members draw their initial responses to policy questions. The aim is to broaden the claims-making capacity of the Parliament by compositionally reflecting the electorate in its membership.

Assigning individuals with the primary responsibility for cultural change denies the reality of liberal democratic political systems that produce conflicting incentives and permission structures. Within the complex dynamics of the Australian political system non-traditional political actors may continue to access and entrench adaptive behaviours that perpetuate rather than transform institutional culture. For example, the current structure of the Australian parliamentary system encourages women politicians to adopt more stereotypical masculine leadership traits in pursuit of election and promotion.

Understanding that identity is partially socially constructed and responsive to environment is critical to shifting focus from candidate-based cultural change to transformative systems change. Increasing the diversity of individual representatives in parliament will not necessarily result in those individuals making different decisions, focusing on different issues, or prioritising values differently. Instead, shifting the burden of responsibility for representation onto the institution of Parliament - its processes, networks and informational ecosystem - may enable different outcomes to occur.

Supporting institutional change does not reduce the agency of individuals within the system, but the opposite: removing barriers to participation and creating new opportunities to explore broader ranges of knowledges enables individuals to access more diverse performances of their identity. In turn, the institutional claims-making capacity will increase, supporting and strengthening the necessary cultural change for parliament to fulfil its representative purpose.

Traps of identity politics

Apply across the political spectrum; may operate concurrently. Geographic, cultural and social sorting exacerbate the effects of these traps.

Collapses multiple identities into homogenous groups reliant on conformity to an ideal;

Links identity markers to a set of values and ideas;

Ranks relative levels of privilege and marginalisation.

Essentialism/ mega-identities

Ignores identity differences as a matter of principle;

Relies upon the ‘abstract individual’ to remove biases through procedural, but not structural, equality of opportunity;

Supports cultural change as the primary method of systemic transformation.

erasure/ ‘meritocracy’

Identity traps example: Liberal individual

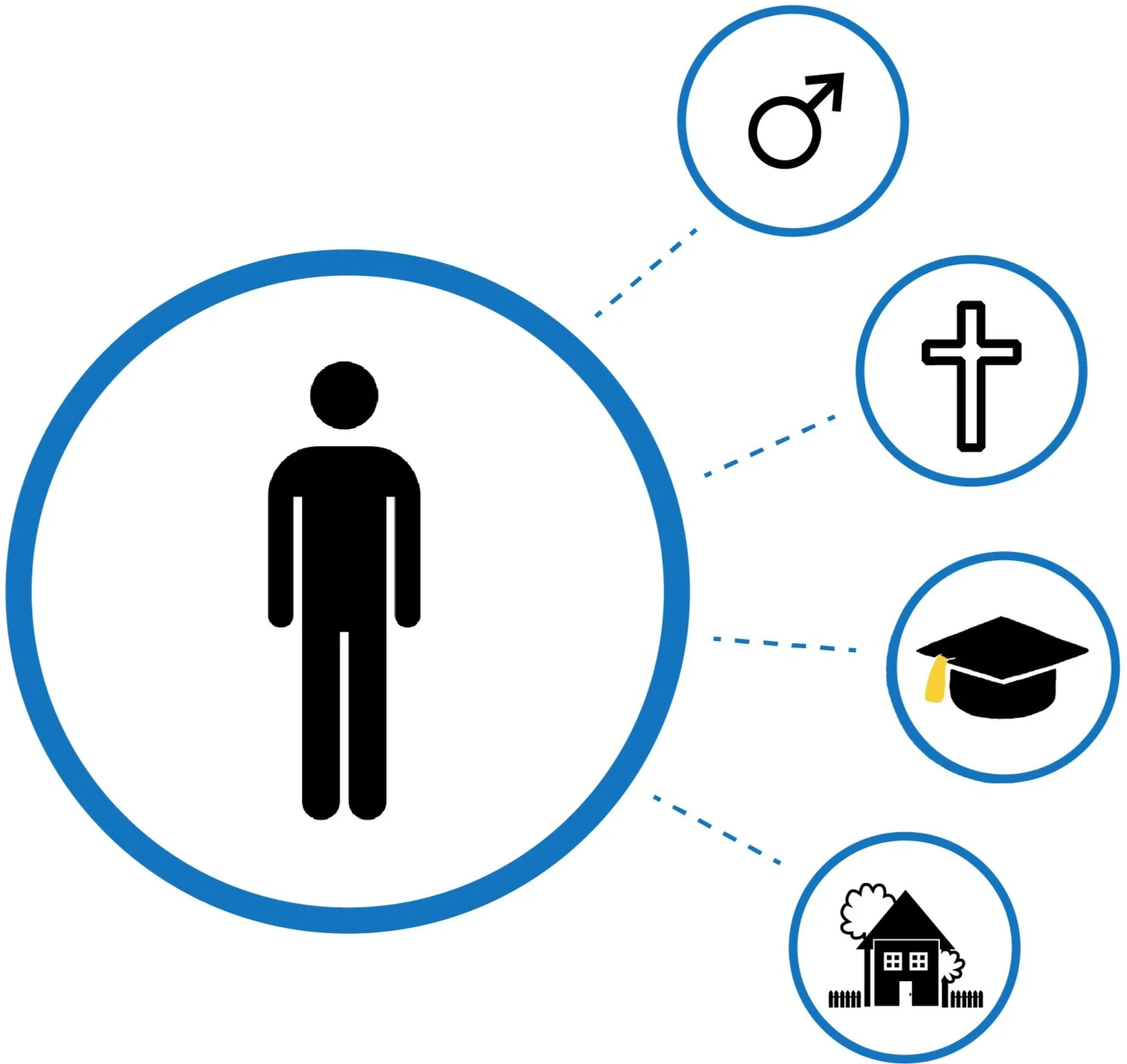

The liberal individual forms the conceptual basis of Australia’s political and legal system. It theoretically creates a tool for standardised policy analysis by endowing all individuals with universal, natural characteristics of freedom, equality and rationality.

The normative characterisation of the liberal individual used in contemporary Australian political and economic modelling still reflects the characteristics of the 17th century ideal British voter: an Anglo-Saxon, Christian, educated, landowning married man with children.

Using such a singular, abstract, understanding of individual motives and decision-making as the foundation for system design and policy development risks obscuring the differential effects these decisions may have on those who do not share these characteristics.

In institutional terms existing power dynamics are perpetuated by the disproportionate value this analysis places on the networks and experiences of those who share characteristics with the liberal individual.